I had high hopes for an equally rewarding and successful journey. In fact, in one way more so, because Ed is physically fitter than Ben was. I’ve been visiting the Himalaya since 1988, but had never gone above 6,000 metres. It’s one of those arbitrary goals I wanted to realise. On this trip I hoped to do it.

Back in December 2009, Ben and I met a local called Phanden Sherpa on our way between Lukla and Namche Bazaar on the first day of our two week trek. Phanden turned out to be a highly accomplished high altitude climber, who has gone on to leverage his stellar climbing CV (summits above 8,000 metres - Everest 9, Cho Oyu 5, Lhotse 1, Dhaulagiri 1) into his own trekking and climbing company, SherpaClimbing.com. Incidentally, his brother Phurenji Sherpa, lives at Mount Cook Village with his family. He played the role of Sherpa Tenzing in the recent movie about Sir Ed Hillary. So in November I gave Phanden a call to work out a little high altitude sojourn to fit within our three week self-guided trekking programme. This picture, in 2009 with Ben and Phanden Sherpa at his tea house in Ghat.

Despite what you might hear, any reasonably fit person doesn’t need a guide or porter in the Solu Khumbu. The place is dotted with villages and often more than adequate lodgings, all connected by centuries old, well graded footpaths. The locals are friendly and speak enough English for you to get by just fine. But if you want to tackle something a bit more challenging, then an experienced guide and porter support can add huge value; and are often essential. This picture, with Ben in 2009, here on Gokyo Ri (5,350m).

Our plan was to get well acclimatised on our own devices up to Everest Base Camp (5,300m), then meet Phanden at a small village a little back down the Khumbu glacier called Lobuje (4,930m). From here he would guide us for four days, first crossing the Khumbu glacier and Kongma La (5,550m), camping a hundred metres beneath the pass on the far side. Next morning we would climb Pokhalde (5,806m) and then descend to Chhukung, before heading the third morning back up above 5,000 metres to camp another night out, prior to me attempting Imja Tse (6,189m, Island Peak) – my chance to finally break 6,000 metres. A good plan, so long as all our flight connections worked, our baggage didn’t go astray en route, the weather in the Khumbu (December is winter) remained settled and we remained healthy as we acclimatised – my fingers were crossed as we departed Wellington on 28th November! This picture, with Ben in 2009, here at 5,400m on Cho La.

Ed and I were met on arrival by Phanden at Kathmandu International Airport. Over a nice cold Everest beer in Thamel we discussed our plans in depth. The bad news was that Phanden now had to guide a much bigger paying group on Mera Peak, so had delegated our project to his brother in law Kami Chiri Sherpa. At first I was disappointed, having looked forward to spending time with Phanden in the mountains. But I needn’t have worried. While Kami had only summited Everest five times (!!!), he turned out to be an exemplary guide – a good communicator, competent and organised, very ‘client happiness’ oriented and, when the going got tough, extremely strong and calm.

Another benefit of having Phanden on the job was that all the red tape stuff was done for us prior to our arrival. Local flight bookings, guide, porter and gear organisation, securing of trekking and climbing permits and arrangement of guide/heli rescue insurance (since the recent fatalities and corresponding fallout - a big ticket item at USD1,200). This meant we were back at the airport before dawn next morning, awaiting our local flight to Lukla (2,800m). Once the morning fog had cleared at the Lukla end we were away and, by lunchtime, on the trail bound for Jorsale (2,800m).

It was on the flight to Lukla that I think it really started to dawn on Ed that he was somewhere very different and pretty cool. While it’s become much tamer than the first time I flew into Lukla back in 1988, when the airstrip was just a gravel strip, our arrival there still got the heart racing. This picture, Himalayan peaks from the window of our plane en route to Lukla.

Our first stop down the line at Jorsale that evening was also a culture shock for him. Since 1995, on my second visit to the Khumbu, I have had intermittent contact with a local Sherpa family. When Ed and I arrived this time, Pasang Dorje and Ang Nimi were in the midst of the last day of funeral ceremonies for their thirteen year old son Lakpa Temba. He had suffered from epilepsy and died tragically a week earlier. The family was also still dealing with the loss of their old Tibetan style home to the recent earthquakes, so our reunion was a tearful and heartfelt one.

While the quakes wreaked havoc throughout Nepal, it was surprising and heartening to see how people were managing to just get on with things, despite the incompetence (or worse) of Nepalese government officials. Pasang Dorje and Ang Nimi had taken a loan and had already rebuilt a home come trekker’s lodge (which had then taken a second hit from aftershocks). During our entire time in Nepal we were not inconvenienced at all by post-quake disruptions.

My own extended family back in New Zealand had pulled together enough money to make a difference to Pasang Dorje and Ang Nimi, so there were more tears when I handed this to them. Deep sadness and loving friendship all rolled into one intense meeting, as Ed and I were off again next morning, bound for Namche Bazaar.

Once across the huge suspension bridge beyond Jorsale, we were confronted by the dreaded Namche Hill. Actually it’s not that bad but, for first timers to the Himalaya, the relentless 650 metre climb to the highest altitude they’ve ever been on foot before (Namche Bazaar at 3,450m) seems like a fairly big deal at the time. Getting well acclimatised is mission critical to an enjoyable trek in the Khumbu. Not everyone understands that, ascending too quickly for their bodies to adjust to the rarefied air. Because the trails are so good in the Khumbu it’s quite easy to make very big height gains quickly – too quickly! This picture, from above Namche Bazaar at dawn, Mount Everest peaks over the Nuptse wall, with Lhotse and Lhotse Shar to the right.

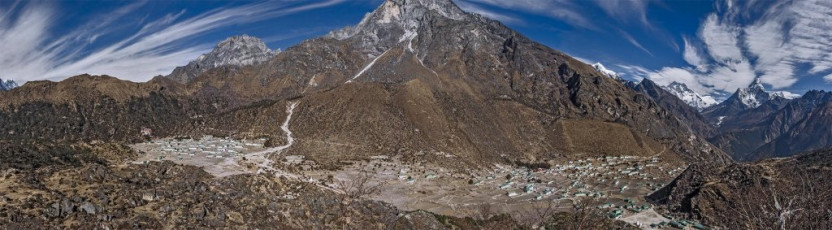

Given what we planned later in our trek with Kami our guide, I was keen to make sure that altitude would not be the factor to hold us back. The key when acclimatising is to not go too quickly and to take opportunities to “climb high, sleep low”. Being my fifth visit to the Khumbu, I had an acclimatisation plan that I thought should work really well, which proved to be the case. During our 19 days trekking we had nine nights above 4,750m and climbed to seven different viewpoints above 5,000m – great for both acclimatisation and photography. This picture, a view from our first acclimatisation climb to 4,000m above Khumjung (right) and Khunde, with a multitude of Khumbu peaks.

Ama Dablam (6,856m), from above Khumjung.

As we worked our way higher, we came upon other trekkers again and again at the lodges. Soon we had several rivals for Dumble – a card game played a lot up in the Khumbu. We also had plenty of trail time to discuss the meaning of life, the universe and everything – no smart devices or TVs to get in the way – although that was our choice. Sadly or otherwise, digital technologies have well and truly arrived in the Khumbu now. A common sight is a porter chatting into his device on the trail, or a local standing out on some promontory trying to get a signal. This picture, from left, Ama Dablam (6,856m), Malanphulan (6,573m), Kantega (6,685m) and Tamserku (6,770m) from Mong La (3,950m).

Another one of our acclimatisation climbs. This one the view northeast from Nangkar Tshang (5,000m - directly above Dingboche). Makalu (8,485m) is left of centre.

It was evident as we walked, that Ed had caught the photographer bug. Armed with my partner Cathy’s camera, he was shooting in every direction. During our trek I was able to teach him the basics of manual photography, which was a bonus for us both. He now has a good insight into how to make a camera really work to its potential and I got to share one of my life’s passions with my son. This picture, Yaks on the trail before Dughla (4,620m).

Another one of our acclimatisation climbs, this one above Lobuje (4,930m), up rocky Lobuje Hill (5,200m), which continues further upwards towards Lobuje East.

Day ten saw us at Everest Base Camp. It’s possible to go more quickly than this, but we took a less trodden, less direct, but more scenic route, enjoying mostly settled, clear conditions throughout. Although December is winter in Nepal, with the associated risk of a big snow dump blocking trails and passes, generally more settled, clear, dry weather at this time makes it a great time to be there. Especially so given that there is only a third or less trekkers in December compared to October and November. During peak times the Khumbu gets really busy, making the experience the reverse of what I seek in the mountains.

A classic sunset vista from Kala Pattar - from left, Khumbutse (6,665m), Changtse (7,553m), West shoulder, Everest summit (8,850m) and Nuptse (7,861m).

After Everest Base Camp we were pretty sure that our acclimatisation had gone well. Now it was time for the business end of the trek. Kami met us at Lobuje on the afternoon of Day eleven. He had arranged for Chhongbi, a 21 year old from his village below Lukla, to bring tents, cooking gear and food up from Chhukung, a village on the far side of Kongma La, the next day. Everything was in place and the good weather continued to hold. I could see that Ed was getting psyched up. He now knew how hard it is climbing above 5,000 metres, especially with a pack, so he knew his biggest challenge was now at hand. This picture, a view of fantastic cloud formations coming off Nuptse, from Lobuje.

After breakfast we set off for Kongma La, some 600 metres above us. This picture, taken above Lobuje, looks across the Khumbu glacier to the route up to Kongma La. Pokhalde is on the right.

First Kami led us across the labyrinth of the Khumbu glacier, picking our way through vast ridges of rubble-covered ice and surface lakes. The climb to Kongma La (5,550m) was relentless but straight forward and the views both ways from the pass were definitely worth the effort. This picture, on the Khumbu glacier with Pumori behind.

On the east side we could see a tiny square and an ant wandering about. Chhongbi had arrived on time and was busy preparing camp. He’d come up 700 vertical metres to our camp site at 5,450m from Chhukung, carrying in excess of 35kg – respect.

Down at camp we spent the rest of the day eating and keeping hydrated, while pondering our objective of tomorrow – the rocky bulk of Pokhalde, towering more than 350 metres above us. Once the sun set the temperature plummeted. This was the highest I’ve ever slept. Actually, at 5,450 metres we didn’t get much and it was a relief to get going on the climb before dawn next morning.

Dusk at base camp. Makalu (8,485m, centre), with Imja Tse (6,189m) beneath and in front of it.

Summit day was Ed’s fifteenth birthday. He had never worked so hard on a birthday, as the pained and gaunt look on his face on the way up testified. This picture, sunrise from about 5,600m. Sunlight illuminates the big boys first - Makalu and Lhotse.

But his grin on the summit of Pokhalde (5,806m) summed up why we climb. Although very exposed in places, essentially Pokhalde was just a rock scramble for us. We encountered no snow on our route at all.

From the top I enjoyed a very special moment with Ed, as well as spectacular new perspectives of one of the most beautiful mountain scapes in the world. This picture, just below the summit of Pokhalde. Further right are Pumori, Lingtren, Khumbutse, Nuptse and Lhotse.

After our descent we had food and packed up camp. Chhongbi set off before us with a monster load, which I pondered more than once as we worked our own way down through huge rock formations and expansive, bare, golden hillsides, wearily reaching Chhukung 750 metres lower in mid-afternoon. This picture, Pokhalde summit view back down to our camp site. Kongma La is left, between shadow and light. Nuptse and Lhotse soar overhead and Makalu stands out on the right skyline.

After a better sleep at lower altitude in a bed we headed up again, along the moraine of the Nuptse glacier towards Imja Tse. Until now Imja Tse had looked like nothing much at all, dwarfed by 8,501m Lhotse beside it and 8,485m Makalu behind. But as we got closer it began to take on a more impressive persona. Also, as we neared base camp, the wind began to pick up a little. This picture, Imja Tse (6,189m). The route to its summit is from the other side.

Chhongbi taking a breather on our way from Chhukung to Imja Tse base camp - fair enough!

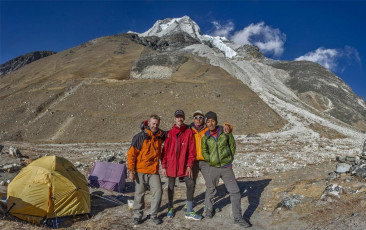

That night my bladder decided to torment me. Between lights out and departure for the summit at 2am it drove me from my sleeping bag nine times! After the first four Ed suggested I use our 1.5 litre water bottle rather than exiting the tent into sub-zero temperatures, which tended to kick start my now well entrenched dose of the Khumbu cough. Excellent idea. The next five pees nearly filled it. This picture, at base camp (5,000m) with Imja Tse behind.

With virtually no sleep, it was adrenalin and ambition that got me up and away into the sub-zero darkness. As we climbed in the glow of our headlamps the biting wind intensified. We zigzagged up through bluffs for about 800 metres before reaching the base of the ice. It was colder than I had experienced ever before and unfortunately, it was still an hour away from dawn. We didn’t want to venture up into the icefall until we had some visibility, but despite double gloves, while we waited my hands were quickly freezing. All I could do was slap my hands against my thighs and jog on the spot, performing a demented form of high altitude haka – for 45 minutes nonstop, to keep semi warm. This picture, at the base of the 200m headwall, with the summit.

At last there was just enough light to carry on up, so we got out our crampons. As I fumbled with numbed fingers to get mine on one of the supposedly super tough plastic toe bindings suddenly shattered. I swore into the freezing wind. I couldn’t believe it but now, on reflection, I realise just how cold it was up there for that to happen. I’ve never had this problem, even in the depths of a winter blizzard, back in New Zealand.

Enter the super guide. Kami calmly swapped sets of crampons and improvised a way to effectively use my broken one. At 5,800m, suffering sleep deprivation, dehydration (our water supplies had frozen) and a hacking cough, I struggled with basic tasks. This just became more pronounced as we climbed higher. It was an enlightening experience, indicating to me that climbing Himalayan peaks might not be the best use of my climbing time in future. It’s a journey of suffering, where my technical performance became well below normal. While it was great to get so high, the process wasn’t very satisfying at all. This picture, Kami doing a bit of rope management with the summit ridge behind.

Nevertheless, now with crampons on and roped up, Kami led the way up into a world of tortured ice bulges, cliffs and crevasses for a hundred or so vertical metres. This flattened out into a fairly large shelf, at the far end of which was a two hundred metre headwall. The gradient was fifty degrees or so, with a fixed line still in place, left over from the season just been. We jumared up this, Kami ever attentive at each anchor point to make sure my jumar was safely transitioned. He was effectively babysitting me and, in my depleted state, I was happy to just go with the flow. This picture, looking along the summit ridge (away from the summit) to Ama Dablam.

At 6,100m we reached the summit ridge. Each looked over the lip and along the very steep and exposed traverse across hard ice to the summit, a further ninety metres up. As the bitter wind whipped the fixed line Kami said a little anxiously “Route no good today.” There was no argument on my part – Kami had climbed Imja Tse fourteen times already; and my tolerance for suffering had reached its limit. Before we commenced our retreat I took some photos. It was 8.15am.

This picture, looking back down the headwall from the summit ridge.

This is a view looking down the icefall from about 5,900m at the bottom of the headwall. Ama Dablam is far right.

The descent was easier, but the intense cold never completely left me until 12.30pm, when I flopped into our warm tent, back at base camp. In hindsight, I should have had a down jacket with me. My New Zealand clothing system just wasn’t up to high altitude Himalayan winter conditions.

This picture, back below the snowline at about 5,700m.

As I lay gazing out the tent door an entertaining scene unfolded. While waiting for us with Chhongbi back at camp, Ed had sensibly put my pee bottle outside to thaw out in the sun. Now it was the consistency of a slushy – soft enough to expel from the bottle, which he did. From nowhere an enthusiastic flock of Himalayan Snowcocks appeared, greedily guzzling down the lime green blobs scattered around. Those birds really knew how to take the piss!

Our return to Chhukung that afternoon was slow. My 53 year old body wasn’t interested in speed of any kind, but we’d completed the hard yards now and had five days, more than ample time, to return to Lukla to catch our flight out. I felt satisfied. All aspects of the journey had met or exceeded expectations, but I’ll leave the last words with Ed, taken from his final entry in our shared daily journal. “This trip has been mentally and physically insightful. I’ve learnt how far I can push myself; and how I see our Western culture has changed. Things we take for granted at home are privileges here in Nepal – a hot shower, a bug-free environment. Coming here has planted a seed. I hope to make something of it back home.”

Unfortunately it hasn’t made him keep his bedroom any tidier, but time will tell …

Post script: My youngest son Will turns fifteen at the end of October 2017, so we are bound for Kathmandu and then the Khumbu at the end of November. This picture, a view from the Swayambunath of Kathmandu.